Sitashwa Srivastava on the secrets of building a startup (and knowing when to kill a startup)

Welcome to the second edition of The Bellwether Club – trica’s interview series with India’s most prominent entrepreneurs and investors, to uncover the real stories behind their success. Our guest in this chapter is Sitashwa Srivastava, co-founder and Co-CEO of global investment platform Stockal.

The Bengaluru-based startup has raised $9 million in Series A funding, and is all set for global expansion. But Sitashwa’s journey to becoming a flag-bearer for the investment ambitions of the Indian and South East Asian community started almost two decades ago.

In a long, candid conversation, Sitashwa rewinds his journey to me – revealing what led him to building Stockal, and the valuable lessons he has learnt on the way:like the fact that when there is subjectivity, it is harder to scale. Or the one factor that makes the difference between building a traditional business and a new-gen tech startup.

Interestingly, Sitashwa says his DNA was in getting good marks, not in building businesses. He grew up in Allahabad in an academically oriented family. An outstanding student at school, he graduated in Electronics Engineering from the Harcourt Butler Technological Institute, Kanpur, in 2004.

“Growing up, I actually wanted to be a tennis player. But I wasn’t very good. So, fortunately, my family made sure that I didn’t go down that path,” he recollects.

The path he did finally go down was that of entrepreneurship, and what a journey it has been!

When did you start thinking about entrepreneurship? You started up first when it was not common as it is today.

After graduation, I worked at a software company called Perot Systems in Noida for two years. I was nurturing some ideas of entrepreneurship, and went to an accelerator in Ahmedabad to see what I could make of it, this was back in 2005. If you got selected, you won Rs 20-25 lakh cash prize, and you spent six months there, developing whatever idea you came up with.

A friend and I went with a project we had developed in college, around eye-testing equipment. When I got selected, I thought about quitting my job. But there was no tech entrepreneurship ecosystem in those days, so the perceived risk was high. My parents urged me to do an MBA, because everyone was doing it at the time.

I went to Great Lakes Institute because it was a one-year MBA there and their fee at the time was in my budget too. I enjoyed that one year more than the four years in engineering – I liked the professors, friends and acquaintances I made.

After graduating from Great Lakes, I again wanted to start up. I had a few ideas. But I had to pay off the loan I had taken for my MBA. So I worked at Cognizant in Bangalore, and paid off my loan in two years.

The Bangalore startup ecosystem had started forming then. TiE’s Bangalore chapter was very active. They used to run EAP – Entrepreneurship Acceleration Program. While working at Cognizant, I applied for it and won the EAP contest in 2008.

What was the project at the time?

It was a B2B creative services marketplace. ![]() In 2008, digital agencies were not a thing. So it was more like an advertising agency on the cloud. Creative people who otherwise did not have a professional outlet and the companies which needed creative people for their campaigns, could find each other at our platform.

In 2008, digital agencies were not a thing. So it was more like an advertising agency on the cloud. Creative people who otherwise did not have a professional outlet and the companies which needed creative people for their campaigns, could find each other at our platform.![]()

Everything was done remotely, on the cloud. We launched it in 2008 and ran it until 2014-15.

Did you raise any money in that business?

We raised a small amount in angel investment.

At work, I was saving some money. Simultaneously, we were trying to raise funds. At the EAP, we had great exposure among investors. But since we were still working full-time jobs, nobody took us very seriously. If I had quit my job, I may have been able to raise funding.

Today people just take the plunge. But you made sure that you had money to fall back upon. Some of the largest startups in the world – like Amazon, Facebook, Microsoft – were all secure from day one. Either their founders came from rich families, or they had early angel investments to protect them.

In my case, I had the right social environment. Even though nobody in my family was into entrepreneurship and the risk was high, my parents were quite supportive of me starting up. If they had any anxiety, they didn’t show it to me.

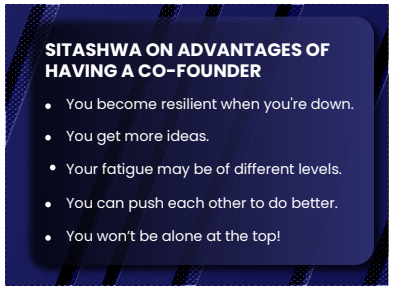

This was the second time I wanted to quit. The first time, everybody told me to do an MBA. Now I have done that and paid off my loan as well, everybody knew that I was determined. Ultimately it’s about getting an idea which resonates with you so much that you can’t do anything else.

The startup was registered in late 2009 – as ‘CreADivity’ (this later rebranded to Jade Magnet). My B-school friend, Manik Kinra, quit his job and came back from the UK so that we could start up together. It was a bigger risk for him – he had more liabilities; he had a family and had bought a house.

The startup was registered in late 2009 – as ‘CreADivity’ (this later rebranded to Jade Magnet). My B-school friend, Manik Kinra, quit his job and came back from the UK so that we could start up together. It was a bigger risk for him – he had more liabilities; he had a family and had bought a house.

When did you feel that you needed to do something else, that the idea of Jade Magnet had lived its life?

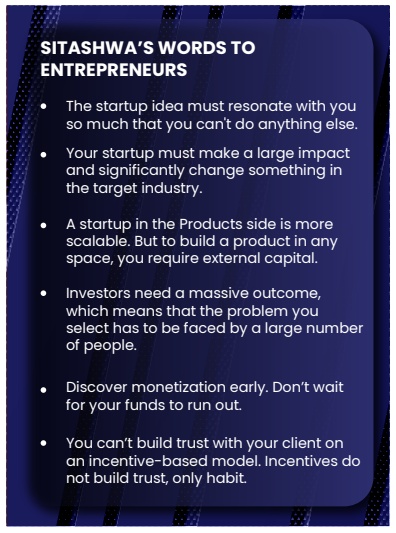

Companies often get to a stage where it stops growing, but it won’t die unless you kill it. We had realised over time that it would be tough to raise capital (for Jade Magnet), because ultimately it was a services’ marketplace.

Even today, services marketplaces haven’t really done well for investors. Even Elance and oDesk in the US merged (to form UpWork) and only now started doing well, 20 years after starting,

(We were in the market for funds around the time when Flipkart and big ecommerce marketplaces were in the market for funds. And there were only those many VCs!)

I think this is a very big lesson for founders: if you’re starting a business which has no history of getting funded or scaling, it will keep generating cash and you have to be happy with it. If you launch a startup, it will have a lot of scale and can be funded. You realised that you can’t scale that business.

With marketplaces, it’s tough to scale without external capital, because your margins are razor thin. The difference between a services marketplace and a classic services business is in the margin. In a classic business, you focus on gross margin. In a marketplace, you’re a facilitator.

We had made friends with a lot of investors; but we knew they would never invest. Anything which has any degree of subjectivity in the outcome is tough to scale. If a service-person from Urban Company comes to fix your AC, it is a binary outcome – whether it is fixed or not. There’s no subjectivity there. But if you’re providing a more complex service like design – like making a landing webpage or writing a video script or creating content – there is subjectivity.

![]() When there is subjectivity, it is more difficult to scale. We realised it only over time. We were enamoured by the idea of creative crowdsourcing.

When there is subjectivity, it is more difficult to scale. We realised it only over time. We were enamoured by the idea of creative crowdsourcing. ![]()

Crowdsourcing was new at the time, and we were among the early players. Crowdsourcing initiatives work only when it is curated and managed. The digital ecosystem in those days was not advanced enough to be able to curate at scale. If I were to do it today, I would do it differently with automated curation.

With machine learning, it would be easier.

Precisely.

The other problem was that collecting money digitally in India was extremely difficult at that time, especially from SMEs. We have had a business promoter, who got a logo done by us, walk into our office and directly give us a bunch of currency notes as payment!

![]() Digital payments were almost absent then. So it was difficult to get paid. Indian SMEs are anyway notoriously late in payments, or they were at least in those days; so it was tough to sustain at times.

Digital payments were almost absent then. So it was difficult to get paid. Indian SMEs are anyway notoriously late in payments, or they were at least in those days; so it was tough to sustain at times. ![]()

By 2013-14, we started realising that it won’t scale. We were 3-4 years old then and hadn’t raised venture funds. If you’re that late, it becomes tougher to raise money, because everybody’s seen you and experienced you, and people would have taken their call on whether you are fundable or not. So the only way is to increase margins and reduce scale. Thus we started acquiring bigger customers. We became an outsourced creative shop for many big brands. We had 15 people internally and a few thousand people in the community who would do the creative work. Late 2014, I sold Jade Magnet to another digital agency.

Can you take us to Day Zero of Stockal? What led to you and your co-founder meeting?

Vinay (Bharathwaj, Co-founder of Stockal) and I met when I was still running Jade Magnet and Vinay came from a hedge fund background and was running another startup – which was a client of Jade Magnet. Both of us were entrepreneurially inclined and connected well.

INSERT IMAGE OF BOTH CO-FOUNDERS HERE WITH THIS CAPTION: Sitashwa Srivastava with his Stockal co-founder Vinay Bharathwaj

I’m sure many founders go through this: they have 5-6 ideas but don’t know what to go through with. How did you decide?

One is, of course, you have to become passionate about the idea. But you also need to make a large impact. It should significantly change something in whichever industry you are targeting.

And one of the key things of being able to raise funds – from an investor perspective – is that you have to create a massive outcome for them, which means that the problem you select has to be faced by a large number of people. So that was the framework: is it large enough or not?

I thought angel investing would scale a lot. Another idea was to use the wisdom of the crowds to get investing signals. A fund of $40 million was launched in the US in 2011 to invest in Twitter sentiment signals. So we figured that funds are investing in alternative intelligence.

It all comes down to your ability to measure that intelligence and make it actionable for the investor. We decided to pursue that. But this problem exists with retail investors, not hedge funds. If there is a flood in Cairo, I don’t know whether the price of rice is gonna go down in India. People know this from experience, not digitally-served insights.

![]() We felt that there is existing intelligence, which, if delivered in digitally available insights, will benefit many. So the idea was to create a decision-making tool using intelligence from alternative data, create algorithms to collect intelligence from alternative data, and then deliver it to retail investors.

We felt that there is existing intelligence, which, if delivered in digitally available insights, will benefit many. So the idea was to create a decision-making tool using intelligence from alternative data, create algorithms to collect intelligence from alternative data, and then deliver it to retail investors.![]()

We were able to raise angel capital from some very supportive early investors, and built the first version of the product.

I wrote anonymous blogs for a year, sending them to traders, interviewing people in the US and Asia, just to see the kind of interest we are able to get, so that when we launched the product, we would have an audience for it.

Stockal was founded in May 2015, and the first product came out around February 2016 – it was a search engine, like Google for ideas.

Our target market was the US, because big data was not organised enough in India then, and if we do it for the US market, we can bring it to India later. Slowly, we transformed from a search engine to an iOS app. We had early users and traction; but although the back end and the algorithms were all decent, the front end needed to be redone and that took another six months.

Did your tech background help in this?

Nope. Both, Vinay and I, have done engineering; but we don’t have a tech background so to say. So we got a CTO and built a team.

The money we had raised initially got over by the time we re-built the front end. So we kept raising (angel investment) on an ongoing basis from our existing investors. The new version did much better and we got around 70,000 users quickly.

We expanded the product to do a lot more in terms of the intelligence that we were developing and delivering. We wanted people to trade on our app, not just get intelligence from it. So we built trading into this app: let people import their portfolios from various brokerage accounts, get intelligence on the app, and then trade on it.

The trade would go through the brokerage account. That’s where we monetized.

That’s a lot of technology work, right? Because you are entering into somebody’s secured system to actually execute a trade on your app.

Most of this runs on API calls with the brokerages so not all the technology and execution is internal to us.

Having said that, we were still processing 8-10 million data points every day, and running out of money by late 2018. So we urgently had to raise more or find monetization (our investors could only help us so much!).

But the US brokerage ecosystem was going towards zero commission. Our entire model was based on the concept that retail investors probably did not pay for intelligence but will trade. (When you trade, you’re paying a few dollars to your broker. I get commission from the broker, because I originated that trade for the broker.) But if we had to get money from the brokers, we had to be regulated. The cost of getting regulated is high, and if you do get regulated, you will not make money in that model.

So you were at an even more complex crossroad than before.

Yes, because now we had burnt through our capital, had more employees (our team was in India) and we had a product which was becoming bulkier and bulkier. A common problem with product folks is that if nothing is working out, you build more features. We built a lot of things, which ultimately, were not useful at all.

So we went back to the drawing board, and figured we should build a product for advisors. Robo advisory – an automated service that advises on managing investments by first gathering information through online surveys – had become a thing by then, and it could empower human advisors with tools of trade and automation.

And that was a turning point.

Yeah. A lot of people (in India) used to ask us – “Can I use your app to invest in the US?” We ignored that. You need to have an account with one of the US brokers to trade on the app. We didn’t even have an Android version. That’s how unfocused we were on the India market.

![]() One of our advisors was shocked to learn that you couldn’t invest in US stocks if you were in India. “It has to happen at some time! So why don’t you think about this more?” he said. That’s when we started digging into the opportunity and found that it was a large one. Whether we do it or not, somebody will do it. Since we knew the US brokerage ecosystem well by then, we felt that we were the right people to do this.

One of our advisors was shocked to learn that you couldn’t invest in US stocks if you were in India. “It has to happen at some time! So why don’t you think about this more?” he said. That’s when we started digging into the opportunity and found that it was a large one. Whether we do it or not, somebody will do it. Since we knew the US brokerage ecosystem well by then, we felt that we were the right people to do this. ![]()

You’d already done the difficult parts right? Of getting the relationships there and the transactions.

Right, and 50% of the product was also ready.

You already had Zerodha and ICICI Security coming up; Indians were probably wiring more money outside than ever. Did you wonder why nobody was already doing it?

Yeah. The first question that we wanted to answer to ourselves was – why is it already not a thing? So we dug into the history of global investing in India, and found that ICICI had actually tried doing something in 2010-11 but it had not taken off.

We tried to understand the inherent issues. We studied LRS (liberalised remittance scheme), the RBI mandate that you can invest up to a quarter million dollars a year outside India. We were taken aback when we saw that in 2012-2013, Indians sent about $1.5 billion abroad. In 2017-18 it was more than $11 billion. By the end of 2018, it was around $6 billion from the people who invested in 2018-19 alone. So we could see that something big was happening!

And this money was probably sitting in some equity or some portfolio or mutual fund across the world?

No, this was getting spent – not even getting invested. The LRS for education fee payment and travel itself was very high. It went from $144 million in 2013-14 to $3.6 billion in 2018-19. In 2019-20, it was $4.9 billion. Overseas expenses were increasing, but the money for investing was not growing at all. Out of about $11 billion, it was about $400 million for investing (in 2018).

So they are earning in India, spending across the world, and not taking any advantage of what’s happening globally in their investment portfolio?

Nothing at all! We realised that there are logistical issues in sending money abroad; only UHNIs were doing it. Also, global brokerage platforms were not keen on onboarding Indian people. Anyway, the US is a very big market; and how will they even understand Indian KYC?

So you decided to pivot and take Indian investors to the world. Can you take us through what you are offering today with the Stockal ecosystem?

We think of ourselves as an infrastructure company, building products to solve problems from a US/global perspective: like KYC, AML (anti-money laundering), quick account opening, etc.

![]() In India, we had to solve problems in banking, inward remittance, and outward remittance. The ecosystem is very advanced; the banks are developing slowly.

In India, we had to solve problems in banking, inward remittance, and outward remittance. The ecosystem is very advanced; the banks are developing slowly. ![]()

We also decided to extrapolate to the entire emerging markets. We started from India because it’s complex enough to address, and you can get to a certain scale. Solutions you build for India can be replicated in many ways.

So the other smaller countries (smaller by population) – did they also have the same challenges that India had?

Pretty much, because there were capital controls. For example, in Indonesia, which has a sizable population, there’s lots of brokers and banks, and money goes abroad a lot. But due to capital controls, you can’t send more than $25,000 a month. So banks had a compliance process; there is friction, and the banking ecosystem is not well-evolved.

There are also opportunities in Southeast Asia and the MENA. All the services are expensive, including brokerage – from $10 to $50 for a trade! So there is massive price disruption possible. If you use technology, you can bring costs down and increase scale. We are also getting into around 25 countries in Eastern Europe.

So will you do B2B2C or B2C or both?

It’s a mix. You need to build trust in B2C. But it has to be monetizable – a proper business model without zero commission. An incentive-based model can’t build trust, only a habit. Thus we went to B2B2C. We went to brands, brokers, banks, and wealth managers, who were already established, and urged them to use this as an asset class for their customers.

You earned money from it and shared your fees with them. Do you still use a broker in the US to execute that trade? Or do you already have an account in the US and you do the trade for them?

There will be a US broker, and the Indian investor will get a US trading account sitting here with minimal documentation. You can open an account in 10 minutes. You still need a US broker to help you with execution, custody clearing etc.

You work with the banking ecosystem in the source country and with the investing ecosystem in the destination country. Then you pick the products that you think people want to invest in. Whichever country you are doing this in, you need the support of local banks – same in India.

We started with just equity. India was the first market we were sourcing customers from, and India wouldn’t allow margin overseas. So we just did classic delivery rates.

We started with stocks and ETFs (exchange traded funds). Then we created a portfolio marketplace called Stacks. We got some very high quality asset management companies, portfolio management companies to build stacks or manage portfolios for the Stockal platform. So a customer can now access high quality advice, even with $1,000 investment or a $500 investment. Now we’re adding products – like funds, fractional funds, bonds, cash management etc. We’re becoming multi-assets as we expand geographically.

As we wrap up our chat, I ask Sitashwa about the next big thing in the tech world: cryptocurrency. He is excited about the future possibilities, and believes that regulations will grow to understand such innovations.

“The underlying infrastructure for crypto or decentralised finance will be core to what will happen in the next 10 years in finance,” he says, adding that a lot of the existing infrastructure will adapt to newer ways of finding efficiency – from crypto and the underlying infrastructure on which crypto/decentralised finance is created.

I am not a bit doubtful that Stockal will be part of the most important chapter in India’s tech-startup story. In fact, Sitashwa’s story reminded me of our earlier guest at The Bellwether Club, Umang Bedi’s words – that “If you can build a product for one billion people you can take it to seven billion.” Stockal grew from an India-focused product to one that is now expanding across continents, and their success story writes testimony to the power of resilience and perseverance in entrepreneurship.